Trails (MonVi) Mac OS

The Mac is dead…long live the Mac!

- Trails (monvi) Mac Os 11

- Trails (monvi) Mac Os Catalina

- Trails (monvi) Mac Os Download

- Trails (monvi) Mac Os X

Last week marked two major shifts in Apple’s personal computing platform: the introduction of Macs built around Apple’s own custom silicon, and the launch of Big Sur, the latest update to the venerable macOS operating system.

And of course, while we want to enjoy the here and now of these latest changes—and, probably, carp a little bit about the things that we don’t like—it’s also worth it to look at the path forward from here: the reverse trail of breadcrumbs laid out and leading, not back to where we came from, but on to the future.

The Oregon Trail is an educational computer game developed by Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger in 1971 and produced by MECC in 1974. The game was inspired by the real-life Oregon Trail and was designed to teach school children about the realities of 19th century pioneer life on the trail. The Oregon Trail - Macintosh Garden. Set up your wagon and travel through the undiscovered American West of the 19th century! Sequel to The Oregon Trail, which is available in floppy and CD-ROM editions. 'Oregon Trail II' PC/Mac CD image Otii.iso (487.7 MB) English version for PC (Windows 95-XP) and Mac OS 7.1 to 9.2.2.

Take the A14 to the M1

Apple’s claims about the performance of its debut Mac processor, the M1, have been met with equal parts amazement and skepticism. As is hardly surprising for a company as versed in marketing as Apple, the graphs and figures promised blockbuster improvements on not only the company’s earlier Macs, but also curves that outstrip much of the PC market. (After all, why make the change if it’s not significant?)

Trails (monvi) Mac Os 11

Those claims will be put to the test soon enough, and though I’m relatively confident that Apple isn’t going to brag about improvements that it can’t back up, there will certainly be places where the new Macs do better than others.

That said, even early numbers have pointed to these being jaw-dropping speed increases, of the kind that only come along once in a while. And it’s worth thinking about where the Mac goes from here: as my colleague Jason Snell pointed out, this is just the first chip in a whole family, and Apple’s only targeted its lower-end consumer Macs so far.

One advantage to those of us in the prognostication business is that the Mac’s roadmap is a little more predictable now. We’ve seen the kinds of improvements the company makes year after year to the iPhone and the iPad, the constant iteration of its processors, the gains it makes year over year in performance, graphics, machine learning, and so on. The Mac has hopped on that same treadmill, no longer bound to a third party’s schedule, and with results like those, there’s a reason it’s never getting off.

Go Big Sur or go home

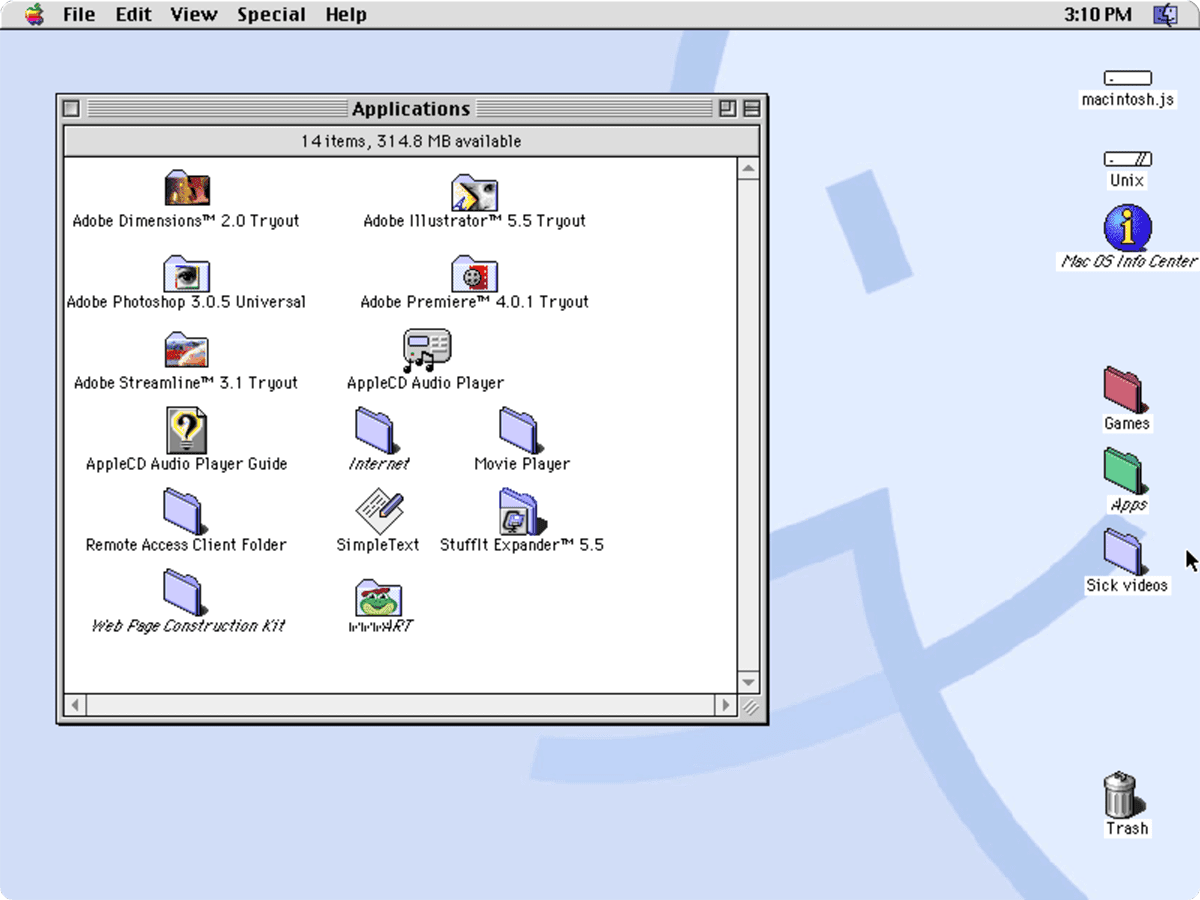

In the nineteen years since Apple launched Mac OS X—more than half the platform’s life. now—the company has issued more than a dozen major software releases. Sometimes they’ve been hugely significant, other times they’ve felt more modest. But, in many ways, Big Sur seems like the most important update since that initial Aqua interface arrived to replace the classic Mac OS.

Trails (monvi) Mac Os Catalina

Design is a big part of that, because it’s something that Apple spends a lot of time on. There have been refinements of the macOS interface over the last two decades years, but it’s often felt more gradual. This time around, Apple seems determined to make everything old new again—perhaps indiscriminately, at times.

But this too is patently Apple. The company has always enforced a top-down approach to the look, feel, and behavior of its operating system, and its users, for the most part, trust the company to make good decisions. Sometimes missteps happen, and they get reeled back, and that too is likely to happen with Big Sur, though don’t expect the big changes to get reversed: this is Apple charting the course for its personal computing operating system for the foreseeable future. No, the Mac and iOS are still not destined to become one and the same, but the company is clearly looking to make them feel even more strongly related than they already do: not just from the same clan, but from the same immediate family.

Theseus statement

At this point, the Mac is like the fabled ship of Theseus. Slowly upgraded over the last 36 years, seeing replacements in processor architectures, underlying software, and pretty much every other component, it’s somehow both instantly recognizable as the same device that appeared on a stage with Steve Jobs in 1984…and yet also completely different.

Trails (monvi) Mac Os Download

And that speaks to a larger point of the Mac: it’s not just a product, it’s an ideal. In the same way that every new iPhone seems like it gets closer to some platonic concept of “the smartphone,” the progression of the Mac shows it approaching that fundamental core of what personal computing means. It might seem like the company should have made even more progress as the Mac nears the 40-year mark, but this curve is asymptotic, and I doubt that anyone at the company will ever conclude that the current version is perfect and can never be improved.

Trails (monvi) Mac Os X

This is just what Phil Schiller meant when he said, more than half a decade ago now, that “The Mac keeps going forever.” Come whatever processor architecture, whichever form factors, and any software underpinning that may, the Mac’s work is never done, its watch never ended. The Mac you knew may be gone, but there’s always another just like it around the corner.